I think the title question is one that many of us have asked ourselves at some point or another in our lives: why are we afraid, truly? This question is primordial to understanding our actions and decisions because fear often seems to dominate our thought processes, and it appears inescapable. Many have said in the past that successful people know how to handle their fears, and I would agree – but how do they do it?

Uncertainty. More specifically, fear is intrinsically (and perhaps causally) tied to uncertainty in a way that renders uncertainty our key element of interest. Indeed, consider this interesting relationship. People tend to fear many things, but among the most prevalent are failure, the unknown and inadequacy (none mutually exclusive). All three have, as you have likely guessed, an aspect in common: they reside in the realm of uncertainty. One fears failure because she is uncertain that she will or has the capacity to succeed; one fears the unknown because, by definition, the unknown is clouded by the shadows of uncertainty; one fears inadequacy because she is uncertain that she has what it takes to be enough. In all of these cases, if the person knew with certainty that they would succeed, that the outcome would be good and that they were adequate, they would not be afraid.

The horrifying monster of uncertainty that looms above us with a wide, black smile is, unfortunately, immortal whilst we are mere mortals.

So, we can draw an important conclusion from this assessment: we ought to become the kind of person who is tolerant of uncertainty. Indeed, if I am able to handle the uncertainty with a high degree of confidence and stress management, then I will not be paralyzed by my fear; I will, in fact, surpass it. If, however, I cannot handle it, then I will likely succumb to this fear.

Think about it: your ability to think ‘I don’t know what the future holds in this situation but I am willing to accept all outcomes and deal with them as they arise‘ is an extraordinarily powerful mindset to have over ‘Oh goodness, what if I they ask me a question I didn’t prepare for and I mess up the job interview?‘ The former breeds calm and confidence whilst the latter inspires anxiety and self-doubt. The former is a person who is tolerant of the uncertainty associated with their uncertain future; the latter is a person who is anxious at the thought of not knowing what the future holds.

But it is easier said than done, isn’t it? Being able to tell yourself (and believe) that you can handle the uncertainty ahead takes a certain degree of confidence that is most effectively built by the acquisition of resilience. Put simply: launch yourself into uncertain situations and learn how to swim. The more you succeed, the more mental toughness you can nurture within yourself that, eventually, will result in a more confident self.

It is quite easy to see how these connect: having resilience means that you have certainty that you can achieve difficult things because you have done so in the past. Therefore, when a new uncertain (and potentially challenging) situation arises in the future, you are aware that you can handle it because you have done similar things in the past.

Now, this is not to say that fear can be completely eliminated. Sadly, it cannot. But learning how to manage our fears cannot be done by wishing them away. Fears have grip and they return every time that we let them, unwanted and suffocating.

Yet, resilience helps with another crucial factor in fear: the dreaded, terrible pain. I think anyone who tells me that they are not afraid of suffering is a liar, first and foremost to themselves. Whether the pain is physical or mental, we fear it because of its unpleasantness. Napoleon Bonaparte wisely said, “It takes more courage to suffer than to die,” because suffering represents prolonged pain whilst death may be terrifying for a moment, but in the next we are dead and we can no longer feel the fear and pain of life.

The saying that “Life is suffering” is, I would argue, overrated and over-simplified. Rather, it should read, “Life contains a certain measure of inescapable suffering which humanity will go through despite their best efforts to avoid or mitigate it” – though perhaps this one is less catchy than the former.

Needless to say though, the understanding that suffering is an inescapable reality of life helps us understand that, since it is inevitable, perhaps the wisest course of action is to learn how to handle it as well as expected rather than fear it. I often like to think about it in terms of a “pick your poison” kind of mentality: no matter what life you choose, you will experience pain – so embrace that which you choose to do and look ahead with the intent of handling whatever painful obstacles rise in your path.

Learning how to be tolerant of uncertainty – which helps us realize that whatever kind of suffering lies in the unknown darkness, we will overcome – is the best solution to the management of fear that I have developed thus far.

The horrifying monster of uncertainty that looms above us with a wide, black smile is, unfortunately, immortal whilst we are mere mortals. This is to say that no matter what we do, no matter how much technology we innovate, perfect visions into the future are not possible. If you are religious, perhaps you believe that God (or some divine entity) has such knowledge – but faith is coined ‘faith’ for the very specific reason that it does not have an undeniable factual basis, without which free will would be compromised. But this is a conversation for a later date.

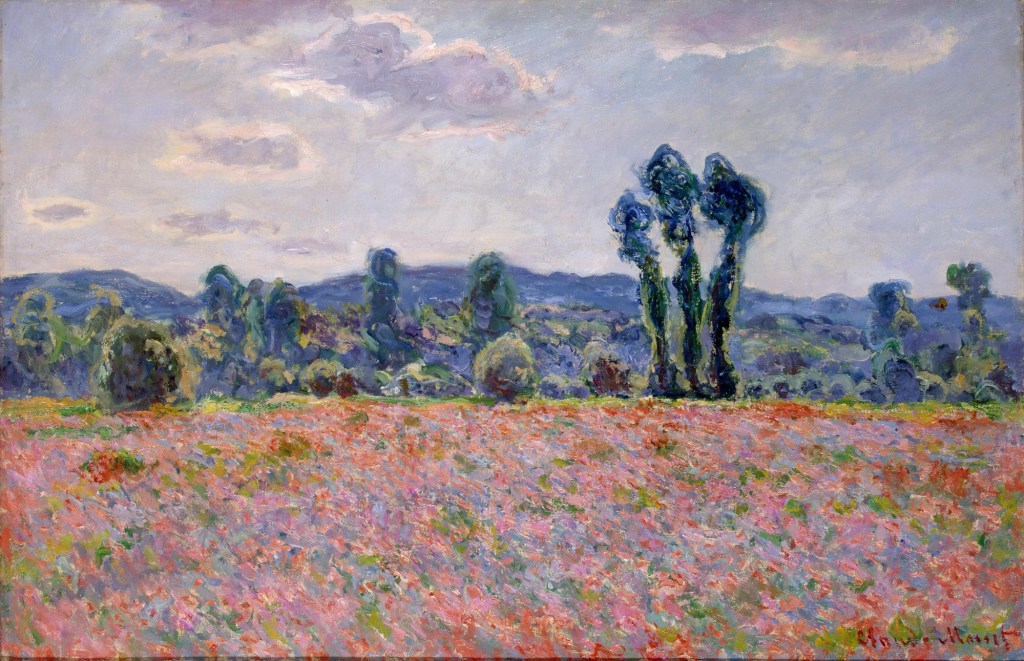

The veil in Nicola Samori’s Il rigore di Girolamo is, in many ways, the dark shroud of uncertainty that prevents us from seeing anything beyond our immediate presence. But it is also a shroud that, instead of being a burden upon us, can be conducive to appreciating the beauty of life itself. Can you imagine how boring it would be to know everything? To never experience excitement, trepidation, surprise?

We ought to become the kind of person who is tolerant of uncertainty.

Uncertainty, whilst it does breed fear, also breeds the exciting and joyful nature of life. Think about being in school and being notified that your grade has been submitted for your latest paper. Perhaps you are nervous (I know I always was) but when you open the grade and it is an A+, the next thing that floods through you is profound relief and pride. If you had known your grade though, you would have not felt fear – but neither would you have felt joy, gratitude, relief.

Those who know me know that I am an adamant proponent of balance. As an Aristotelian, the Golden Mean in ethics shines my path in life – including with fear and uncertainty. There is reason to be afraid, but there is also reason to be calm, and finding that fine line between a reasonable (and in fact, productive) level of fear and confidence has significantly increased my happiness and quality of life.

Perhaps it will with yours, too.